The following is a very general overview of patents, and is not intended to apply to any particular situation. Rather than relying on these generalities, please consult with me about the specifics of your situation.

Generally, a patent is a government-issued document that grants a related group of exclusive rights to the patent’s owner. In particular, a patent empowers its owner with the rights to exclude others from making, using, or selling, in that country, or importing into that country, anything that falls within the scope of any valid unexpired claim presented in that patent. Most governments grant patents to encourage their owners to provide detailed and empowering written disclosures (which also are presented in the patent) of innovations to the public, thereby continually increasing the public’s knowledge base. Although granted patent rights can provide a powerful incentive to researching and developing innovations, they are of limited duration, and typically expire within 20 years of the filing of an application for the patent.

Except as noted, my communications generally focus on U.S. patents.

In the U.S., there are three basic classes of patent applications:

Because the Utility class is by far the largest (roughly 96% of all U.S. patent applications), except where noted, it is the primary focus of my communications.

The Utility class includes two types of applications: the provisional (a.k.a. “informal”) patent application and the non-provisional (a.k.a. “regular” or “formal”) patent application.

The range of patentable subject matter is very wide. For United States utility patents, patentable innovative concepts can include nearly anything that involves or results from a human-caused transformation and that is reasonably categorized within any of these 4 broad classes:

Within these 4 classes, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office is required to grant Utility Patents that claim useful, novel, non-obvious subject matter (“concepts”) that have been adequately described.

A concept is not considered sufficiently useful if it is merely a law of nature, a physical phenomenon, or too abstract (has no described implementations). Also, the patent application must identify a beneficial use for the concept (other than acting as, e.g., a boat anchor, paperweight, or research curiosity).

A given patent application’s concept is not novel (new) if it was:

Generally, the novelty of a concept is determined based on a comparison to what is “taught” by the prior art, which is basically everything that was known (e.g., everything published) before the origination of the concept.

A concept is obvious if, at the time it was conceived, a person having ordinary skill in the art would have known of art-recognized reasons to modify or combine prior art references, considered as a whole, to arrive at the concept. Thus, although an invention might seem “obvious” from a layperson or engineer’s standpoint, US patent law can be rather strict about what must be proven before an invention can be deemed “obvious” from a patent law perspective.

A Patentability Search often can help reveal whether a concept is novel (and sometimes non-obvious).

A patent application’s description of a given concept is considered adequate if it empowers a person having ordinary skill in the art to successfully (even if non-optimally) implement that concept, in the best manner known to the inventors on the application’s effective filing date, and demonstrates that the inventors actually had the concept in mind.

Generally speaking, Design Patents protect aesthetic (i.e., ornamental and non-functional), novel, non-obvious subject matter as applied to a product and graphically described in an empowering manner.

Some of the most common tactics to harness the power and value of a patent include:

If desired, a patent sometimes can be legally enforced against potential and/or actual competitors to prevent the making, using, offering for sale, and/or selling in, and/or importing into, the country in which the patent is in force, anything that falls within the scope of the valid unexpired claims of that patent.

Such enforcement can often be achieved outside the judicial system, such as via a simple “Patent Pending” notice on the patent owner’s goods.

At other times, enforcement can require the threat and/or filing of a lawsuit alleging infringement of the patent. If the parties are unable to settle a dispute early in the suit, the litigation costs can become very expensive and time-consuming for both parties. Fortunately, the vast majority of patent infringement suits settle early.

Also, for those who do not have the financial means to enforce a patent, patent assertion insurance sometimes can be purchased that will provide the financial muscle to litigate all the way to an enforceable judgment, after being upheld on appeal, if necessary.

Patent rights only arise upon issuance of a patent. Thus, only an issued patent can be legally enforced against competitors. I’d be happy to discuss how I can assist with preparing for enforcing and actually enforcing your patent rights.

Often, the patent owner is willing to allow competitors to make, use, and/or sell the innovation, provided that the competitors pay the patent owner for the right to do so. A document that provides for the grant of such rights and the associated payments is called a “Licensing Agreement”. Please feel free to contact me to discuss how I can help you develop a strategy for licensing patent applications and/or issued patents, negotiating the terms of a Licensing Agreement, and drafting the language of that Agreement.

Sometimes, a published patent application and/or an issued patent can serve as an advertisement of the technical capabilities of the inventors and/or the patent owner. The audience for that message can be potential investors, customers, employees, competitors, and/or suppliers, etc. I’d be happy to discuss how I can help with enhancing that message and/or utilizing the patent document to obtain the desired and optimal impact on the intended audience.

No matter how much money any company spends or what degree of professional assistance it obtains, the potential risks associated with the patenting process are substantial and should be carefully considered before and while pursuing that process.

For example, there are no guarantees how the USPTO will respond to a given patent application, how much time or effort will be needed to convince the USPTO to issue a patent, or what the scope of the claims of the issued patent will be. Similarly, although most of these risks can be well-managed, there are no guarantees how the market will react to an innovative concept, whether a company will be able to successfully license or enforce its patent rights, and/or whether the company will obtain a reasonable return on its investment in the patenting process.

These and other potential risks associated with innovation and the patenting process are significant and should be considered before and while pursuing that process. Of course, utilizing the services of a competent patent attorney often can help lessen some of these risks, but not all of these risks can be eliminated entirely. Thus, it is important that your company recognizes, weighs, and maintains realistic expectations of the potential costs, potential benefits, and potential risks, both throughout the innovation and patenting process and beyond.

Although other forms of protection should always be at least briefly considered to supplement patent protection, patenting is not the best approach in certain situations. For example, sometimes it is more advantageous to maintain an innovative concept as a trade secret than to seek a patent for that innovative concept.

This can be particularly true when:

The general process for obtaining a valuable patent is:

I help my clients with each of these steps of the patenting process.

Because I am admitted to practice in the United States only, my communications tend to center on securing U.S. IP assets, such as U.S. patents. I am happy to discuss my U.S. capabilities, and how I can aid in obtaining patents in foreign countries via my network of foreign patent professionals.

This is a very general overview of patenting. Because it is only general, and not intended to apply to any particular situation, consult with a patent attorney before relying on this explanation.

From the perspective of most individuals, patents are relatively expensive. For example, by the time the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) issues a U.S. patent, a typical patent applicant will have spent a total of at least $15,000 (and possibly considerably more) on the costs of preparation, filing, and, although somewhat deferred, prosecuting the underlying non-provisional U.S. patent application. The costs in most countries foreign to the U.S. can be less, but in some cases are greater (particularly when translations to and from English are needed). Fortunately, a substantial portion of these costs (the prosecution costs) can be deferred until after the patent application is prepared and filed. I would be glad to discuss ways to manage these and all patent-related costs.

I’d be glad to discuss ways to manage these and all patent-related costs.

I am dedicated to avoiding unnecessary overhead and keep my fees very competitive.

Currently, I usually charge $330 per hour. Whenever appropriate, I utilize highly-experienced and well-supervised patent agents, typically billed at $150 – $200 per hour; paralegals, typically at $165 per hour, and/or patent law clerks, typically at $100 – $125 per hour.

A full list of the USPTO’s fees can be accessed here.

Also, I carefully manage my commitments to avoid becoming overloaded, and, when necessary, engage additional highly-competent professionals.

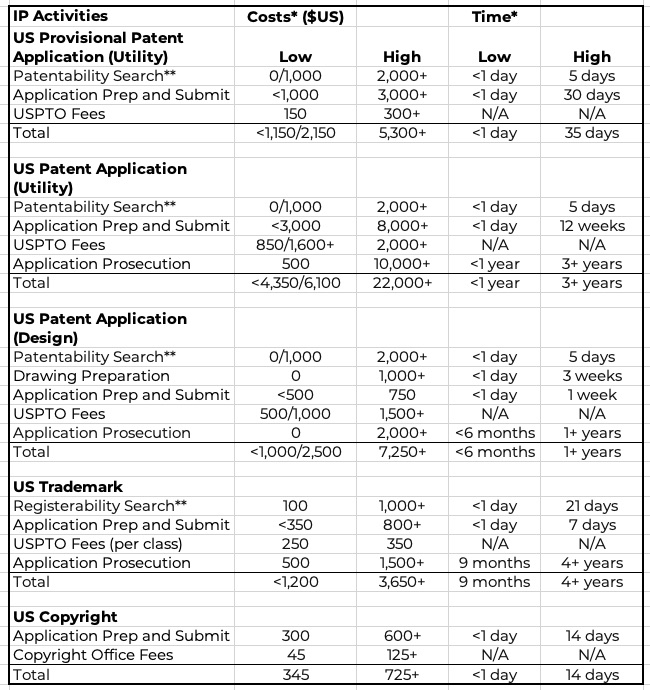

Based on my experiences, the cost and timing ranges listed in the following table are not unusual for the listed IP protection activities:

* Note: Very common activities only for single invention, mark, class, or work. Does not include counseling, opinions, exceptional needs, or certain potential expenses, such as translation costs, formal drawings, express mail, travel, or extension, appeal, or maintenance fees. Keep in mind that expenses, the amount of attorney time required, and provider availability can vary widely depending on the specifics of a particular situation, and thus total costs and durations could differ significantly from these ranges. Do not rely on these cost or timing ranges without speaking to me about your particular situation.

**Although searches are generally recommended, they might not be advised in certain situations.

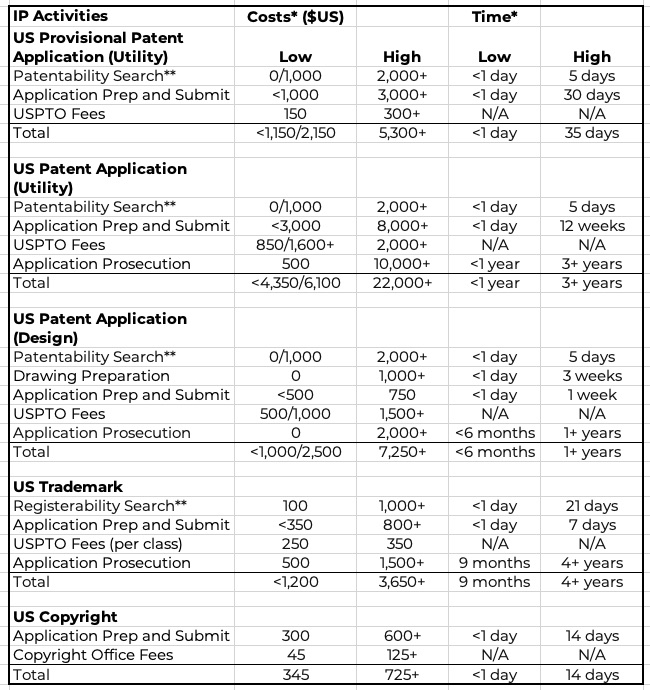

Based on my experiences, the cost and timing ranges listed in the following table are not unusual for the listed IP protection activities:

Note: Very common activities only for single invention, mark, class, or work. Does not include counseling, opinions, exceptional needs, or certain potential expenses, such as translation costs, formal drawings, express mail, travel, or extension, appeal, or maintenance fees. Keep in mind that expenses, the amount of attorney time required, and provider availability can vary widely depending on the specifics of a particular situation, and thus total costs and durations could differ significantly from these ranges. Do not rely on these cost or timing ranges without speaking to me about your particular situation.

*Although searches are generally recommended, they might not be advised in certain situations.

Many countries bar patenting of a concept if there is any public disclosure (and sometimes any attempt at commercialization) of that concept before the filing of a patent application. So generally, the patenting process encourages a “race to the patent office” to protect innovative concepts.

Thus, if there is a desire to preserve the right to file a patent application outside the U.S. (and potentially within the U.S.), I generally recommend the filing of at least a well-written provisional (and preferably a non-provisional) patent application before any disclosure, offer for sale, or commercialization of the innovation occurs.

Once an initial patent application is filed in most countries (including the US), any desired foreign or international patent applications must be filed within no more than 1 year (but immediately in a few countries).

If a US provisional was filed and a US non-provisional is desired, it must be filed within 12 months of the filing date of the provisional.

Despite these time limits, to protect rights in a valuable innovative concept, it is often worthwhile to file some form of patent application as soon as possible. Doing so will provide a filing date that defines what “prior art” can be used against the claims of any non-provisional patent application filed (now or later). Because one never knows when uncomfortably close prior art might emerge, time might be of the essence.

Before making a substantial investment in a patent application, it almost always will be helpful to obtain a professional patentability search. Such a search will attempt to identify some prior publications that describe most or all of the major features of the innovative concept, thereby potentially showing that the concept is not new or inventive. A basic pre-filing version of such a search typically can be completed within 1 to 10 days, and usually costs between $800 and $1500. A basic search can identify certain relevant publications and can help one avoid wasting money trying to patent an unpatentable concept.

A reasonable argument can be made to justify spending even more on an initial patentability search, as follows:

The decision to seek a patent should be thoroughly and carefully considered. The patenting process can be expensive, lengthy, and risky, not to mention frustrating at times. Yet, the rewards can be substantial.

Generally, one should seek a patent if the expected risk-adjusted return justifies the investment in the patent. For some, merely having their name on a patent, or a patent number on their product, is incredibly valuable, particularly when marketing their capabilities to potential investors, customers, employees, etc.

For others, the opportunity to obtain royalties or other forms of licensing revenue from those who wish to manufacture, use, sell, and/or distribute the patented product is an ample justification to pursue patenting.

For still others, the right to exclude competitors from making, using, importing, or selling the patented innovation can provide a sufficient reward for their investment in obtaining the patent.

Despite the beckoning of these potential benefits, recognize that the patent process is moderately risky. For example, not all patent applications result in issued patents, though on a hopeful note, the USPTO’s patent grant rate has substantially increased in the last few years. Although the percentage varies from year-to-year, roughly 75% of original patent applications are eventually granted, while the remaining patent applications are abandoned, with their subject matter potentially dedicated to the public domain. Keep in mind that this percentage includes all original patent applications, including:

Thus, when sufficient resources are properly applied, the likelihood of success with the patenting process can be greatly improved with respect to this 65-70% metric. Generally, the better the patentability search, the better the preparation of the patent application, and the better the prosecution of that application, the greater the odds are that the application will be issued, assuming the applicant remains committed to obtaining that patent. Similarly, the better the business plan, and the better the implementation of that plan, the greater the likelihood that a substantial return will be earned on the issued patent.

Applying my patent valuation techniques, we can work with you to determine potential returns, investments, and risks, and then assist you with developing an appropriate business plan for obtaining the optimal return on your patent investment.

“Invention Promoters”, also sometimes known as “Invention Marketers”, “Invention Brokers”, etc., typically offer to:

Too often, however, customers of numerous unscrupulous Invention Promoters have reported paying substantial sums while receiving remarkably little service in exchange. These rogue Invention Promoters are generally known for high-pressure sales techniques, repeated misrepresentations, and even downright fraud.

Because so many innovators had endured so many ugly experiences at the hands of Invention Promoters, in 1999 Congress enacted section 297 of the Patent Act (35 U.S. C. 1 et seq.), which provides substantial legal remedies for customers found by a court to have been injured by an Invention Promoter.

The USPTO provides warning signs and suggestions for dealing with Invention Promoters and publishes complaints about Invention Promoters. See: http://www.uspto.gov/inventors/scam_prevention/index.jsp

The Federal Trade Commission also provides alerts and tips for avoiding problems with Invention Promoters. See: https://consumer.ftc.gov/articles/invention-promotion-scams

Typically, Invention Promoters are not Patent Attorneys, who must be both licensed to practice by the state in which their primary office is located and registered with the USPTO.

I am not an Invention Promoter. Although I can, among other things, provide patentability searches, prepare and prosecute patent applications, and draft agreements, my primary focus is not raising capital, product development, invention marketing, etc. I can, however, help you identify reputable professionals and resources to assist with your needs in these areas.

In other words, can you “patent it” yourself?

Well yes, you can. It is possible to write, file, and prosecute a patent application for your innovation with no professional assistance.

But just as with performing your own brain surgery or flying your own space shuttle, rarely is it advisable to enter such difficult waters without relying on substantial help from a well-trained and deeply experienced professional.

What makes patenting so difficult? For starters, there are the labyrinthine federal statutes and rules, along with thousands of court cases interpreting those laws, as well as a roughly 6-inch-thick (if printed) set of administrative procedures promulgated by the USPTO.

Moreover, the courts, and particularly the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which hears nearly all patent appeals (and for nearly all practical purposes decides which litigated patents have teeth and which are toothless), have changed directions repeatedly over the last few years in their interpretation of the patent laws, to such an extreme degree that even many patent attorneys have trouble keeping up.

Finally, if they give your company any attention at all, those who might otherwise be appropriate candidates to license your company’s patent will lick their chops at the thought of taking advantage of your company when they realize it obtained its patent without competent legal representation.

If your budget leaves no other options, however, at least read and heed “Patent It Yourself” by David Pressman, which its publishers, Nolo Press, allege is the “world’s bestselling patent book”. Good luck.

I refer to an innovator’s detailed written description of their innovation as an “innovation disclosure”. A well-written innovation disclosure can form a solid foundation for analyzing patentability, risks, and value, and help build a high-quality patent application.

It can be tempting for innovators to provide their patent attorney with a laundry list of trumpeted and fluffed-up attributes of their innovations and call it an innovation disclosure.

Unfortunately, such platitudes, while fine for sales and marketing efforts, usually don’t provide a patent attorney with the relevant information required to build a high-quality patent application.

Instead, at a minimum, a reasonable innovation disclosure typically should provide a:

It is probably safe to say that there are as many successful approaches to business development and product development as there are successful businesses and products on the market. Beyond that, because my primary expertise is in patent and intellectual property law, I limit myself to guiding my clients to potential resources that might be able assist you with developing your business and product.

As you seek assistance, beware that there are a number of unscrupulous Invention Promoters (a.k.a. Invention Marketers, Invention Brokers, etc.) that are generally known for high-pressure sales techniques, misrepresentations, and even fraud. Please use caution before proceeding with anyone who seems to fit this description.

Although I don’t vouch for them or their advice, here are links to several potentially valuable resources:

“From Concept to Consumer: How to Turn Ideas Into Money” by Phil Baker; ISBN-13 978-0137137473; 2008.

“The Mom Inventors Handbook: How to Turn Your Great Idea into the Next Big Thing” by Tamara Monosoff; ISBN-13: 978-0071458993; 2005.

“Do You Matter? How Great Design Will Make People Love Your Company” by Robert Brunner; ISBN-13: 978-0137142446; 2008.

“Raising Venture Capital for the Serious Entrepreneur” by Dermot Berkery; ISBN-13: 978-0071496025; 2007.

“Engineering Your Start-Up: A Guide for the High-Tech Entrepreneur” by James A. Swanson; ISBN-13: 978-1888577914; 2003.

Although litigation is often a fact of life for bigger companies, companies of all sizes tend to experience a bit of disgust at the idea of being threatened with a patent infringement lawsuit. And nearly all companies would greatly prefer to never have to fight such a suit.

Avoiding patent infringement suits starts with avoiding infringement. And fortunately, there are many paths to avoiding infringement, including:

No matter what type of intellectual property rights are involved, I can assist with each of these activities.

In the patent realm, professional searches can lay the groundwork for avoiding and/or resolving many potential infringement disputes. For example, identifying what patent rights are owned by others is the objective of a patent clearance search and opinion. Determining what another’s patent rights cover, and whether those rights are infringed is the goal of a non-infringement search and opinion. And assessing the validity of another’s potentially infringed patent rights is the aim of a validity search and opinion.

Once your company has obtained an appropriate and professional search and opinion, they might want to negotiate with the owner of the IP rights. Yet negotiating why another’s IP rights are invalid or not infringed can be a delicate exercise, which might evaporate the litigation threat, transform it into a lucrative business deal, or escalate hostilities substantially.

So sometimes, it simply can be easier to avoid another’s IP rights altogether, possibly by initially designing around, or later re-designing the potentially infringing product or service. Based on my legal understanding of the potentially infringed rights and my technical capabilities, I guide my clients to successful design-arounds and re-designs.

In other situations, it can make good business sense to obtain authorization to practice another’s IP rights, such as via obtaining an assignment of, or license to, those rights. I have deep experience in negotiating and preparing such agreements.

The variety of potential business agreements is simply astounding. Nevertheless, certain business scenarios appear with such frequency that tools and rules of thumb for crafting relevant agreements have emerged that often can smooth the way and avoid many potential pitfalls.

Perhaps the most common scenario is the need to disclose a trade secret to someone outside the control of your company. In this situation, a Confidentiality or Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) is frequently relied upon. Key to many such agreements can be a clear identification of what must be kept secret, and what uses are allowable for the secret information.

Closely related is the Employment Agreement (and its cousin, the Consulting Agreement). These agreements typically include confidentiality provisions, as well as requirements for assignment of intellectual property rights, assistance with obtaining and protecting intellectual property rights, and possibly a non-compete and/or non-solicitation clause.

Assignment clauses can require that employees, contractors, and/or business partners assign their intellectual property rights to your company. Yet difficulties can emerge when, for example, the resulting assignment documents are drafted incorrectly, sought at the wrong time, or recorded improperly.

When entities agree to work together to research and/or develop technologies and/or products, they typically enter a Joint Development Agreement, which, in addition to the provisions described above, usually spells-out how jointly created innovations, discoveries, and knowledge will be owned and handled.

Once an entity obtains intellectual property rights, it can retain those rights, yet authorize others to exploit some of them, via a Licensing Agreement. The terms of such agreements can vary substantially depending on, for example, business needs, the type of intellectual property involved, the specific rights licensed, and/or the industry. An “exclusive” license allows only a single licensee to exploit the identified right, while a “non-exclusive” license allows each of multiple licensees to do so.

Disputes can arise, for example, in the process of negotiating an agreement involving intellectual property rights, or after such an agreement is in place. Yet careful agreement drafting, and reliance on professional dispute resolution techniques, can avoid litigation while preserving the business relationship and maximizing the value of the intellectual property rights.

Well before infringement of a patent is suspected, it can be worthwhile to verify that adequate financial resources will be available to finance enforcement of the rights to exclude others from practicing the patent. For those who do not have the financial means to engage in patent litigation, often patent assertion insurance can be purchased that will provide the needed financial muscle to discourage or halt infringement.

When infringement is suspected, proceed extremely carefully to: